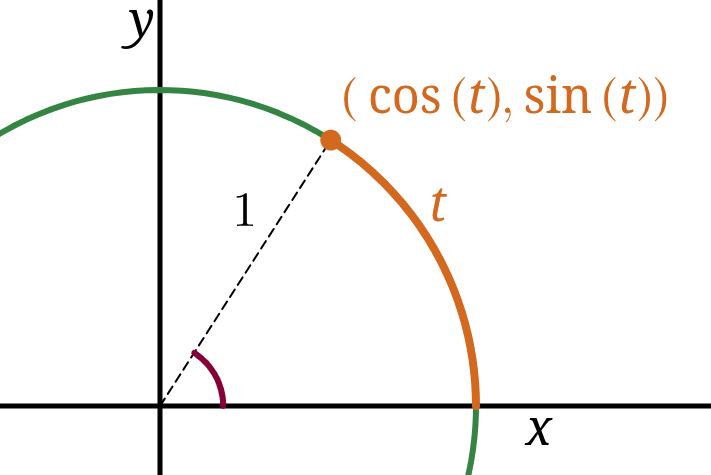

The sine and cosine functions

relate rectangular geometry (lines) to polar geometry (circles).

Given a circle of radius one in the \(xy\)-plane, the unit circle,

and some arc of length \(t\) along that circle starting on the positive \(x\)-axis,

the sine and cosine functions take \(t\) as their input

and return the \(y\)- and \(x\)-coordinates of the other endpoint of that arc as output.

I.e. an arc of length \(t\) along that circle staring at \((1,0)\)

will end at the point \({\bigl(\cos(t), \sin(t)\bigr).}\)

Alternatively, some folks prefer to think of \(t\) not as an arclength,

but instead as an angle, measured in radians, subtended by that arc.

This is how this “unit-circle” perspective on sine and cosine

relate to the classic “right-triangle” perspective.

The sine and cosine functions

relate rectangular geometry (lines) to polar geometry (circles).

Given a circle of radius one in the \(xy\)-plane, the unit circle,

and some arc of length \(t\) along that circle starting on the positive \(x\)-axis,

the sine and cosine functions take \(t\) as their input

and return the \(y\)- and \(x\)-coordinates of the other endpoint of that arc as output.

I.e. an arc of length \(t\) along that circle staring at \((1,0)\)

will end at the point \({\bigl(\cos(t), \sin(t)\bigr).}\)

Alternatively, some folks prefer to think of \(t\) not as an arclength,

but instead as an angle, measured in radians, subtended by that arc.

This is how this “unit-circle” perspective on sine and cosine

relate to the classic “right-triangle” perspective.

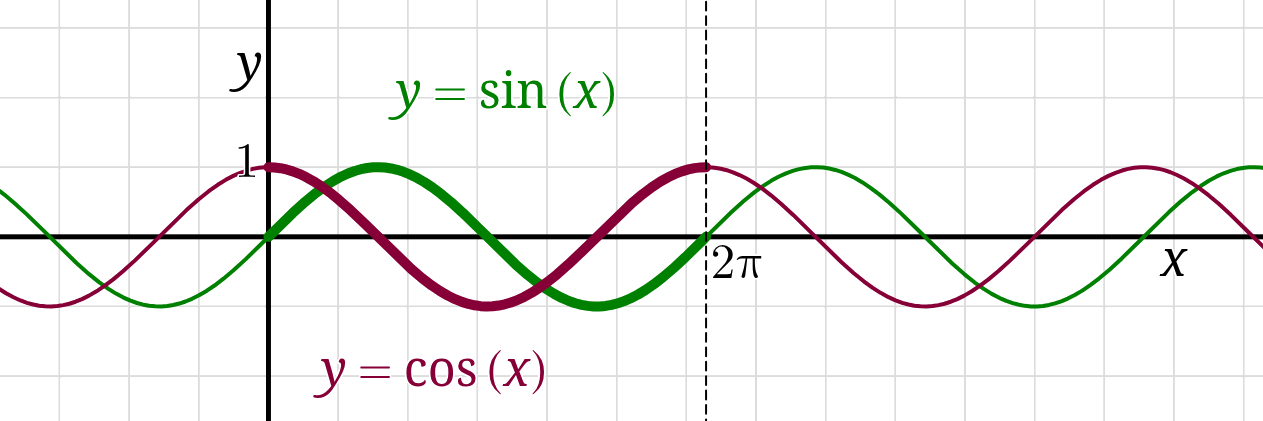

As functions, sine and cosine are periodic:

for any whole number \(k,\) \( \sin(x + 2\pi k) = \sin(x)\) and \(\cos(x + 2\pi k) = \sin(x)\,. \)

That is to say sine and cosine have a principal domain of \([0,2\pi)\)

corresponding to one full circle (one full rotation), and repeat beyond that domain.

The length of that principal domain, \(2\pi,\) is referred to as the period of sine and cosine.

The graphs of sine and cosine oscillate between negative and positive \(1,\)

which we refer to as their amplitude.

As functions, sine and cosine are periodic:

for any whole number \(k,\) \( \sin(x + 2\pi k) = \sin(x)\) and \(\cos(x + 2\pi k) = \sin(x)\,. \)

That is to say sine and cosine have a principal domain of \([0,2\pi)\)

corresponding to one full circle (one full rotation), and repeat beyond that domain.

The length of that principal domain, \(2\pi,\) is referred to as the period of sine and cosine.

The graphs of sine and cosine oscillate between negative and positive \(1,\)

which we refer to as their amplitude.

As functions, sine and cosine have (partial) inverse functions. The inverse of the sine function is denoted either \(\operatorname{arcsin}\) or \(\sin^{-1}\) and the inverse of the cosine function is denoted either \(\operatorname{arccos}\) or \(\cos^{-1}.\) Algebraically: \[ \sin(t) = y \quad\implies\quad t = \operatorname{arcsin}(y) \qquad \qquad \qquad \cos(t) = x \quad\implies\quad t = \operatorname{arccos}(x) \]