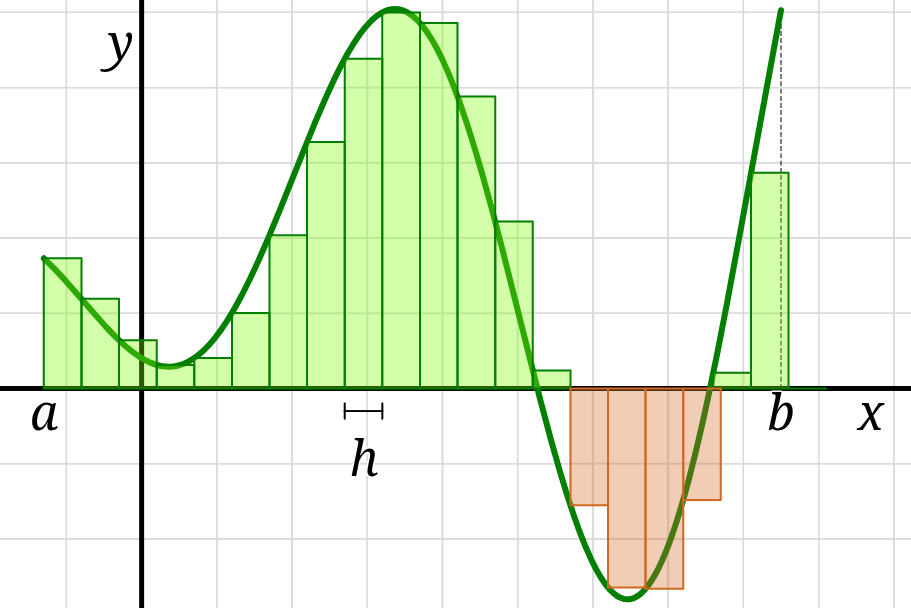

Calculating the exact value of \(\int_a^b f(x)\,\mathrm{d}x,\)

the area of the region under the graph of a function \(f,\)

may be impossible — not every function \(f\) has an elementary antiderivative —

but it can always be approximated to arbitrary precision

by approximating the region as a union of simpler shapes.

A Riemann sum is a sum of the areas of a collection \(n\) of rectangles,

each of the same uniform width \(h=\frac{b-a}{n}\) and each having a height determined by the function’s graph.

As the number of rectangles \(n\) grows larger and larger and the width \(h\) shrinks smaller and smaller,

the value of the Riemann sum approaches the true value of the area of the region under the graph.

For a left-endpoint Riemann sum \(L_n,\)

the left side of each rectangle is defined by the graph’s height,

whereas for a right-endpoint Riemann sum \(R_n,\)

the right side of each rectangle is defined by the graph’s height.

Calculating the exact value of \(\int_a^b f(x)\,\mathrm{d}x,\)

the area of the region under the graph of a function \(f,\)

may be impossible — not every function \(f\) has an elementary antiderivative —

but it can always be approximated to arbitrary precision

by approximating the region as a union of simpler shapes.

A Riemann sum is a sum of the areas of a collection \(n\) of rectangles,

each of the same uniform width \(h=\frac{b-a}{n}\) and each having a height determined by the function’s graph.

As the number of rectangles \(n\) grows larger and larger and the width \(h\) shrinks smaller and smaller,

the value of the Riemann sum approaches the true value of the area of the region under the graph.

For a left-endpoint Riemann sum \(L_n,\)

the left side of each rectangle is defined by the graph’s height,

whereas for a right-endpoint Riemann sum \(R_n,\)

the right side of each rectangle is defined by the graph’s height.

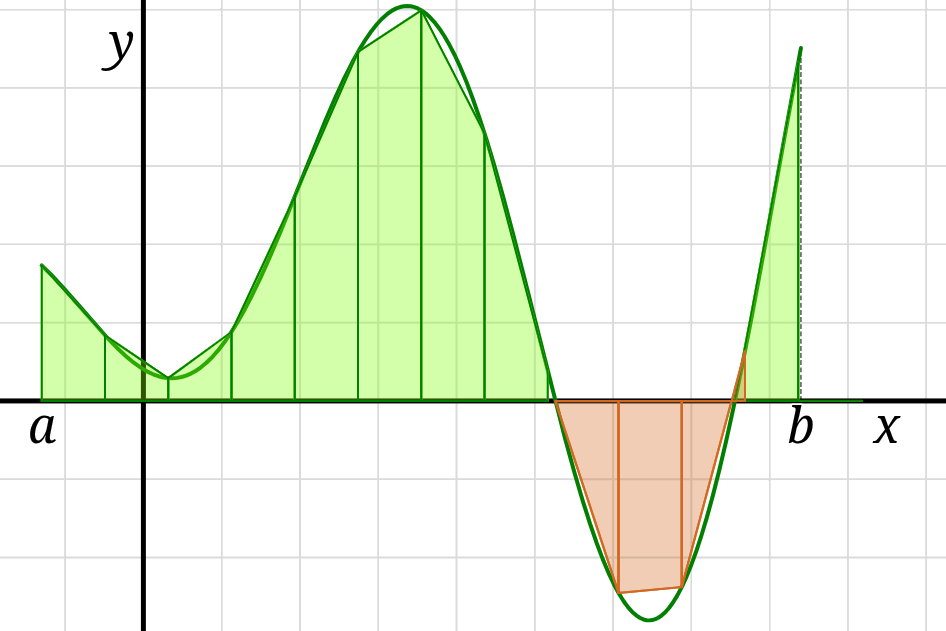

Instead of rectangles, we could use more sophisticated geometric shapes to get a better approximation.

For example, using the trapezoid rule \(T_n\) we approximate the area of the region

as the sum of the areas of \(n\) trapezoids, each of width \(h = \frac{b-a}{n}\)

and each with the lengths of its parallel sides determined by the function’s graph.

\[ \sum_{i = 1}^{n} h \frac{f\bigl(a+ih\bigr)+f\bigl(a+(i+1)h\bigr)}{2} \]

Instead of rectangles, we could use more sophisticated geometric shapes to get a better approximation.

For example, using the trapezoid rule \(T_n\) we approximate the area of the region

as the sum of the areas of \(n\) trapezoids, each of width \(h = \frac{b-a}{n}\)

and each with the lengths of its parallel sides determined by the function’s graph.

\[ \sum_{i = 1}^{n} h \frac{f\bigl(a+ih\bigr)+f\bigl(a+(i+1)h\bigr)}{2} \]