For a function \(f\) and input \(c,\)

\(f(c)\) denotes the value of \(f\) at \(c.\)

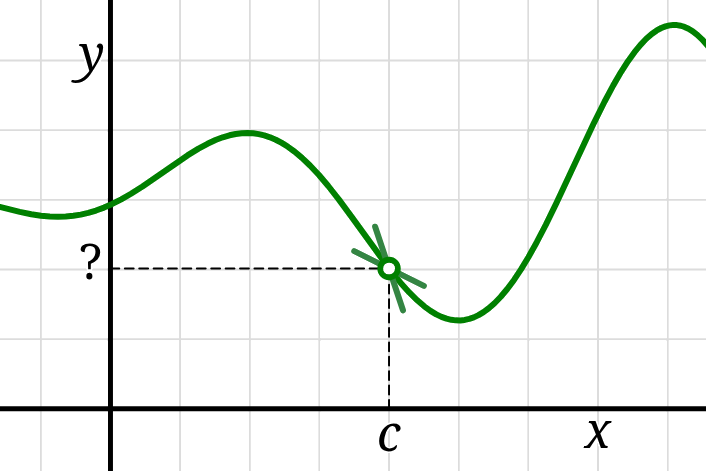

Sometimes though we care more about the values of \(f\)

around \(c\) more than at \(c,\)

especially if there is a “hole” or other peculiarity at \(c\) itself.

The notation \( \lim_{x \to c^-} f(x) \)

is read as “the limit of \(f(x)\) as \(x\) approaches \(c\) from the left.”

It denotes the number the that outputs of \(f\) get closer and closer to

just to the left of the input \(c\) (if that number exists!).

Similarly \( \lim_{x \to c^+} f(x) \)

is “the limit of \(f(x)\) as \(x\) approaches \(c\) from the right,”

and denotes the number the that outputs of \(f\) get closer and closer to

just to the right of \(c.\)

If both of these limits exist and are the same number, say the number \(L,\)

then we drop the superscript \(+/-\) in the notation and simply write

\[ L = \lim\limits_{x \to c} f(x)\,. \]

For a function \(f\) and input \(c,\)

\(f(c)\) denotes the value of \(f\) at \(c.\)

Sometimes though we care more about the values of \(f\)

around \(c\) more than at \(c,\)

especially if there is a “hole” or other peculiarity at \(c\) itself.

The notation \( \lim_{x \to c^-} f(x) \)

is read as “the limit of \(f(x)\) as \(x\) approaches \(c\) from the left.”

It denotes the number the that outputs of \(f\) get closer and closer to

just to the left of the input \(c\) (if that number exists!).

Similarly \( \lim_{x \to c^+} f(x) \)

is “the limit of \(f(x)\) as \(x\) approaches \(c\) from the right,”

and denotes the number the that outputs of \(f\) get closer and closer to

just to the right of \(c.\)

If both of these limits exist and are the same number, say the number \(L,\)

then we drop the superscript \(+/-\) in the notation and simply write

\[ L = \lim\limits_{x \to c} f(x)\,. \]

If it so happens that there is no “hole” or other peculiarity at \(c\) and we have \( \lim_{x \to c} f(x) = f(c), \) then we say that \(f\) is continuous at \(c\). If \(f\) is continuous at every point in some interval then we say that \(f\) is continuous on the interval. If \(f\) is continuous at every point in its entire domain, then we simply say that \(f\) is continuous.

This limit notation is often overloaded to describe the end behavior of \(f.\) The limit \( \lim_{x \to \infty} f(x) \) denotes the number that the outputs of \(f\) approach as \(x\) increases to \(\infty,\) if that number exists. Similarly \( \lim_{x \to -\infty} f(x) \) denotes the number that the outputs of \(f\) approach as \(x\) decreases to \(-\infty.\) Visually, these limits only exist if the graph of \(f\) eventually “levels-out” on the right or left.