"Cultural Studies" is a baggy monster and claims a wide variety of roots and has developed and matured differently depending on ideological affiliations and individual practitioners. As David Richter says, "Cultural Studies is not a theory as such or even a combination of theories; it is not even a single coherent practice, but rather a disparate set of related practices" (1208). Richter quotes Leitch who points out that, "Cultural Studies 'aspired to be a new discipline but served as an unstable meeting point for various interdisciplinary feminists, Marxists, literary and media critics, postmodern theorists, social semioticians, rhetoricians, fine art specialists, and sociologists and historians of culture'" (1208).

Why We Read and What We Read

Again, trying to make a coherent statement about why and what cultural critics read seems problematic given the diversity of projects, so I offer a range of definitions instead, and I'll let you locate the deep structure or patterns that link these statements (I'll note the source of these citations in my next update):

Vincent Leitch:

"The task of cultural criticism is to analyze and assess the social roots, institutional relays, and ideological ramifications of communal events, institutions, and texts. Against the weakening but still regnant scholarly focus on aesthetic masterpieces of canonized high literature, cultural criticism advances the claims of "low," working class, marginal, popular, minority, and mass cultural discourses."

Source forthcoming

Cultural Studies is "an interdisciplinary (and antidisciplinary) field which deals with all aspects of culture in relation to social, political, and historical development and change. It includes work in the mass media, the popular arts, cultural history, the sociology of culture and the arts, class cultures and sub-cultures, cultural institutions, aspects of work and leisure."

Source forthcoming

Cultural Studies is dedicated "to analyzing how discourse is produced, structured and organized, to examining what kind of effects these forms and structures produce in particular people in actual situations, and in how these effects serve the interests of certain groups."

Source forthcoming

"Cultural Studies relates the cultural to the economic, political, and ideological."

Source forthcoming

"Cultural Studies analyzes the social contexts in which a given text was written, and under what conditions was-and is-produced, disseminated, and read. They favor analyzing texts not as aesthetic objects complete in themselves but as works to be seen in terms of their relationships to other works, to economic conditions, or to broad social discourses."

Source forthcoming

"Cultural Studies, as an academic program, would not just study culture, it would study how to create culture, a progressive culture that would, to quote Giroux and McLaren, 'struggle in the interest of greater human freedom and emancipation.'"

Ziauddin Sardar:

"Cultural studies aims to examine its subject matter in terms of cultural practices and their relation to power. Its constant goal is to expose power relationships and examine how these relationships influence and shape cultural practices.

Cultural studies is not simply the study of culture as though it was a discrete entity divorced from its social or political context. Its objective is to understand culture in all its complex forms and to analyze the social and political context within which it manifests itself.

Culture in cultural studies always performs two functions: it is both the object of study and the location of political criticism and action. Cultural studies aims to be both an intellectual and pragmatic enterprise.

Cultural studies attempts to expose and reconcile the division of knowledge, to overcome the split between tacit (that is, intuitive knowledge based on local cultures) and objective (so-called forms of knowledge) forms of knowledge. It assumes a common identity and common interest between the knower and the known, between the observer and what is being observed.

Cultural studies is committed to a moral evaluation of modern society and to a radical line of political action. The tradition of cultural studies is not one of value-free scholarship but one committed to social reconstruction by critical political involvement. Thus cultural studies aims to understand and change the structures of dominance everywhere, but in industrial capitalist societies in particular."

How We Read

If you follow Leitch's lead, then the principle is pretty simple, but the execution is difficult and complex. That is, Leitch reminds us that "each thing is different but relatable to other things" (6) and "Without the totalizing operations, regimes of reason do not come into view. Without the atomizing procedures, forces of construction, resistance, transformation, contradiction, subversion, oppression, and change remain obscured" (Cultural Criticism 8). In other words, it seems that Leitch wants to preserve structuralism's ability to link the ideological system of an individual text with a larger ideological system of a specific historical moment-- what he calls a "regime of reason." But he also wants to embrace poststructuralism's insistence that every text is different, that every text contains its own subversive elements, and that rigorous reading is essential. He doesn't want to erase difference, but he doesn't want to say that every text is independent either.

At its most general level, cultural studies requires you to take a text and link it with the larger social text, "inquiring into the causes, constitutions, and consequences as well as the modes of circulation and consumption of linguistic, social, economic, political, historical, ethical, religious, legal, scientific, philosophical, educational, familial, and aesthetic discourses and institutions" (8).

How do we act on Leitch's imperative? Well, you can certainly rely on other ideological projects like poststructuralism, feminism, Marxism, theories of race and ethnicity, New Historicism, and psychoanalytic strategies that focus on a text as a cultural symptom. But what makes cultural criticism an ambitious project is that it attempts to articulate how these different preoccupations intersect with one another. If there is ever a reading strategy that insists on the textile metaphor of interweaving and overlapping threads, then this is it.

Writing Strategies: A Methodology and an Outline

As noted above, it's useful to think of the aims of cultural studies as you apply the ideological reading strategies noted above, but we can try to weave them.

First, historicize a text (and by "text" we mean any human construct) by situating it in its political, economic, and aesthetic contexts. That is, find out and explain the relationship your text has with other texts of its kind at the time of its production and consumption. Also, what groups of people in that time and place enjoy a degree of power and privilege and what groups are marginalized and dependent? What values, beliefs, attitudes, and hierarchies (ideological positions) do these groups celebrate and denigrate?

Second, note the kinds of discourses your text invokes. That is, what kinds of conversations, debates, issues, and philosophies does your text seem to engage in or respond to? Think about Leitch's list: does your text share language or concepts with political, social, economic, ethical, religious, legal, scientific, philosophical, educational, familial, or aesthetic institutions or practices? You're trying to recognize how your text is "shot through" or intersected by a range of discourses. Your text is a piece of fabric, and you are identifying individual threads.

Third, once you have performed this task of situating the text, you are prepared to ask, "How does (or did) my text function within this context I have described above?" Keep in mind that this is the structuralist or semiotic move, for your text does not have inherent meaning. It only has relational meaning. In other words, the "meaning" of your text is a result of how it functions within a larger system, and your task now is to explain its role in a specific context. To explain its role or function, note how your text is "coded." What images, attitudes, histories, and values are associated with your text? How do issues of social class, gender, race and ethnicity, sexual orientation, regionality, nationality, etc. influence and shape these codes? Does your text reinforce or challenge dominant systems of values, attitudes, beliefs, and hierarchies? How does your text serve interests associated with specific social classes, genders, races and ethnicities, sexual orientations, and

geographies?

Fourth, Leitch encourages us to make the poststructuralist move where we recognize how a text differs from others. We analyze "forces of construction, resistance, transformation, contradiction, subversion, oppression, and change." We note, for example, how a text offers possibilities of resistance (i.e. when a text initially seems to reinforce dominant ideology) or reinforces in subtle ways prevailing hierarchies (i.e. when a text initially seems subversive). This is where we look closely for border-blurring contamination as well as idiosyncratic features that offer subversive possibilities. In sum, this is where we resist the homogenizing impulse of structuralism and note instead the subtle and unique features of a text and its "playful" (in the Derridian sense) possibilities.

In sum, your analysis will shed light on your text, but it will illuminate the historical context as well. We will learn a great deal about social hierarchies, ideological affiliations, social movements, and connections among discourses, institutions, and practices that are operating at a specific time and place. A text is a point of departure, for we learn about ourselves through our specific representations, laws, rituals, institutions, and languages. The aesthetic is inseparable from the social.

What Is Culture?

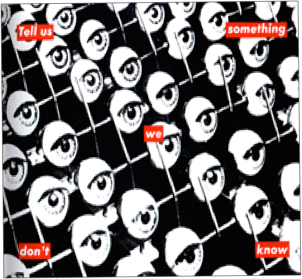

K.I.S.S. of the

Panopticon

Cultural Studies

Central

Border Crossings

PopCultures

Essays on

Cultural Studies

On Culture